POSITIVE NEUROSCIENCE: INTRODUCTION

For much of its history the study of the human brain had a negative tilt, focusing on the atypical, the abnormal, the injured, and (because of the difficulty of accessing the living brain) the deceased. But in recent times neuroscience has taken a positive turn. Technologies like fMRI scans allow researchers to safely observe the healthy human brain in action, and a growing interest in the scientific study of human flourishing has led to the emergence of “positive neuroscience” — a burgeoning field of study that focuses on the nervous system mechanisms that underlie well-being.

The development of this field was significantly bolstered by the John Templeton Foundation’s $5.8 million Positive Neuroscience Project, an initiative led by psychologist Martin Seligman of the University of Pennsylvania. The project awarded grants to 15 groups conducting research at the intersection of neuroscience and positive psychology and raised awareness about recent research and emerging questions in the field.

Read on for highlights from this exciting area of study.

THE SOCIAL, COMPASSIONATE, EMOTIONALLY BALANCED BRAIN

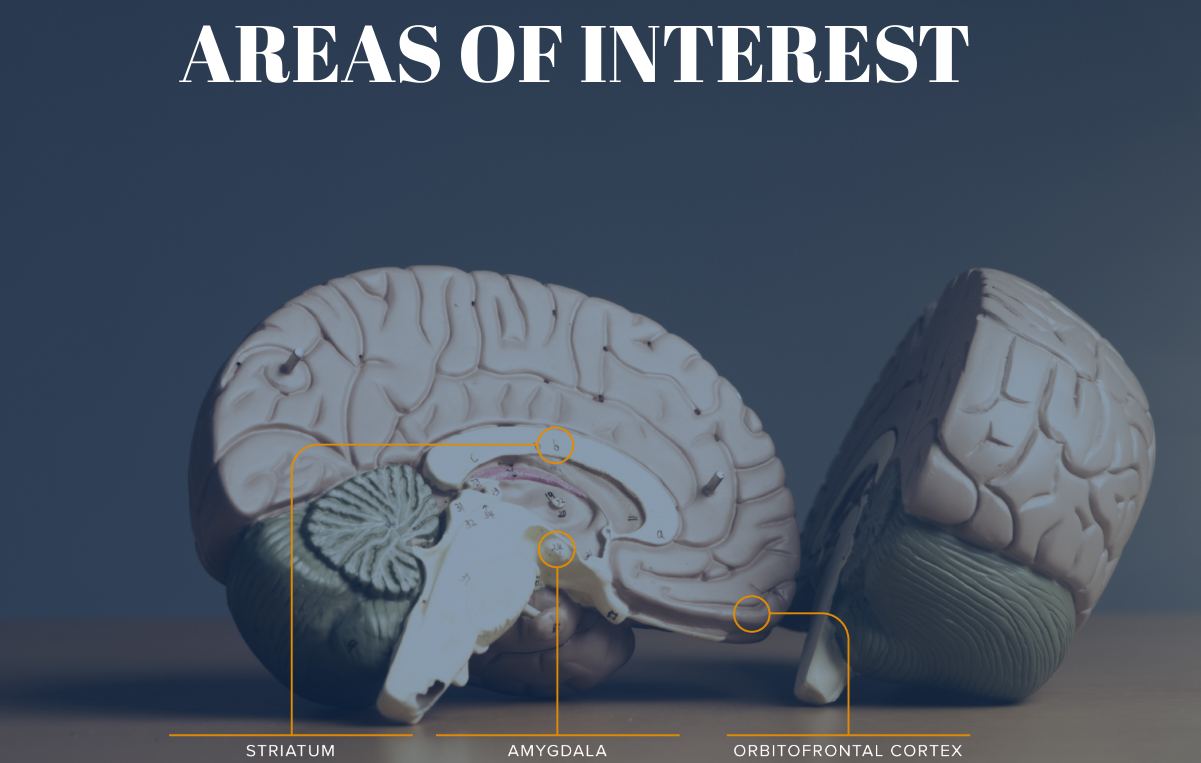

The field of positive neuroscience can seem sprawling, but much of the relevant research can be grouped into a few fields: call them the social brain, the compassionate brain, and the emotionally balanced brain.

A wide body of research on the ways humans form and maintain attachment suggests that humans are “wired to connect”— born with biological mechanisms that allow us to form connections with others — and shows that relationships can change the structure and function of our brains. Several recent studies have examined the neuroscience of parenthood, looking at what happens in the brain as infants bond with their caregiving parents, and how those changes in the brain might affect those infants’ later development. One such study showed that the mothers of one-month-olds who reported having more anxious thoughts about their babies showed lower activity in their substantia nigra, a brain area associated with reward, when hearing their babies cry — and that their children went on to show poorer socio-emotional skills as toddlers.

Other studies have looked at the neuroscience of social bonds between adults. One study found that couples, but not strangers, showed similar patterns of brain activity when they were interacting with one another. Other studies have examined the neurological basis of “social touch” — showing, for instance, that a part of the brain called the posterior insula is activated both when individuals have their arms stroked pleasantly and when they watch videos of other people receiving the same pleasant touches.

Humans’ empathic ability to vicariously experience what others are feeling extends far beyond social touch. Other studies have looked at the neuroscience of compassion and altruism — our ability to guess what other people are feeling and to meet their needs. A series of studies have looked at one class of “extraordinary altruists” — people who volunteered to donate a kidney to a stranger — to try to understand how their brains might differ from average people. One study found that kidney donors were better at recognizing fearful faces; another study found that donors reported greater sympathy when hearing distressing noises than did a control group. Together these studies suggest that the brains of extraordinary altruists are more attuned than average to the needs of strangers.

Social interaction and compassion deal with the ways our nervous system shapes our interactions with others, but positive neuroscience also has much to say, and much to investigate, about our brains’ self-focused processes. Walking down a city street, we may see people hugging or fighting, hear a baby crying, smell food that reminds us of our childhood, and receive a text with sad news—all within a few seconds. People vary in how they respond to situations like these, both in how they perceive these emotional stimuli and in how emotionally affected they are. Over the past few decades, neuroscientists have looked at how our brains respond to emotional stimulation. A key theme in this research is how healthy individuals maintain psychological balance, at the ways genetics and life experience might disrupt this balance, and at how interventions including mindfulness training might restore or improve it.

POSITIVE NEUROSCIENCE: FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Positive neuroscience is still in its early days. Many of the field’s most intriguing findings rest on fMRI studies that had to use small sample sizes to control costs, which have also limited attempts to replicate key studies. There is ample need and opportunity for improved studies that look at greater numbers of participants from more diverse backgrounds. (For instance, some emotional regulation studies have only focused on female participants to avoid having gender difference add too much noise to the data.)

There are also ample new areas to cover. Scientists still know very little about the neurobiological factors that underlie friendship and the different stages of romantic love. There are also numerous questions to be answered about which individual and societal factors can facilitate or inhibit compassion, as well as how new types of interventions might use the brain’s reward system to incentivize various desirable behaviors.

Meanwhile, further study of positive outliers — from kidney donors to musical prodigies — may tell us new things about how their brains differ (or not) from everyday people.