Surveying the economics, neuroscience, psychology, and sociology of giving

People demonstrate generosity in myriad ways, from gifts of time and money to everyday acts of kindness toward loved ones—and even to deeds that involve substantial self-sacrifice, like donating a kidney to a stranger. But we are often nowhere near as generous as we could (or even aspire to) be. In short: although we have the capacity to be generous, we don’t always act generously.

What are the biological, psychological, and social factors that encourage people to give time, money, and assistance? What effects does such generous behavior have on their well-being? What accounts for differences in individual levels of generosity—and what methods might encourage individuals to give more? Are there evidence-based strategies for cultivating greater degrees of generosity? Such questions have given rise to numerous studies, the results of which are described in a new report commissioned by the John Templeton Foundation. The document provides a high-altitude overview of more than 350 studies and meta-studies published in nearly 200 refereed publications between 1971 and 2017.

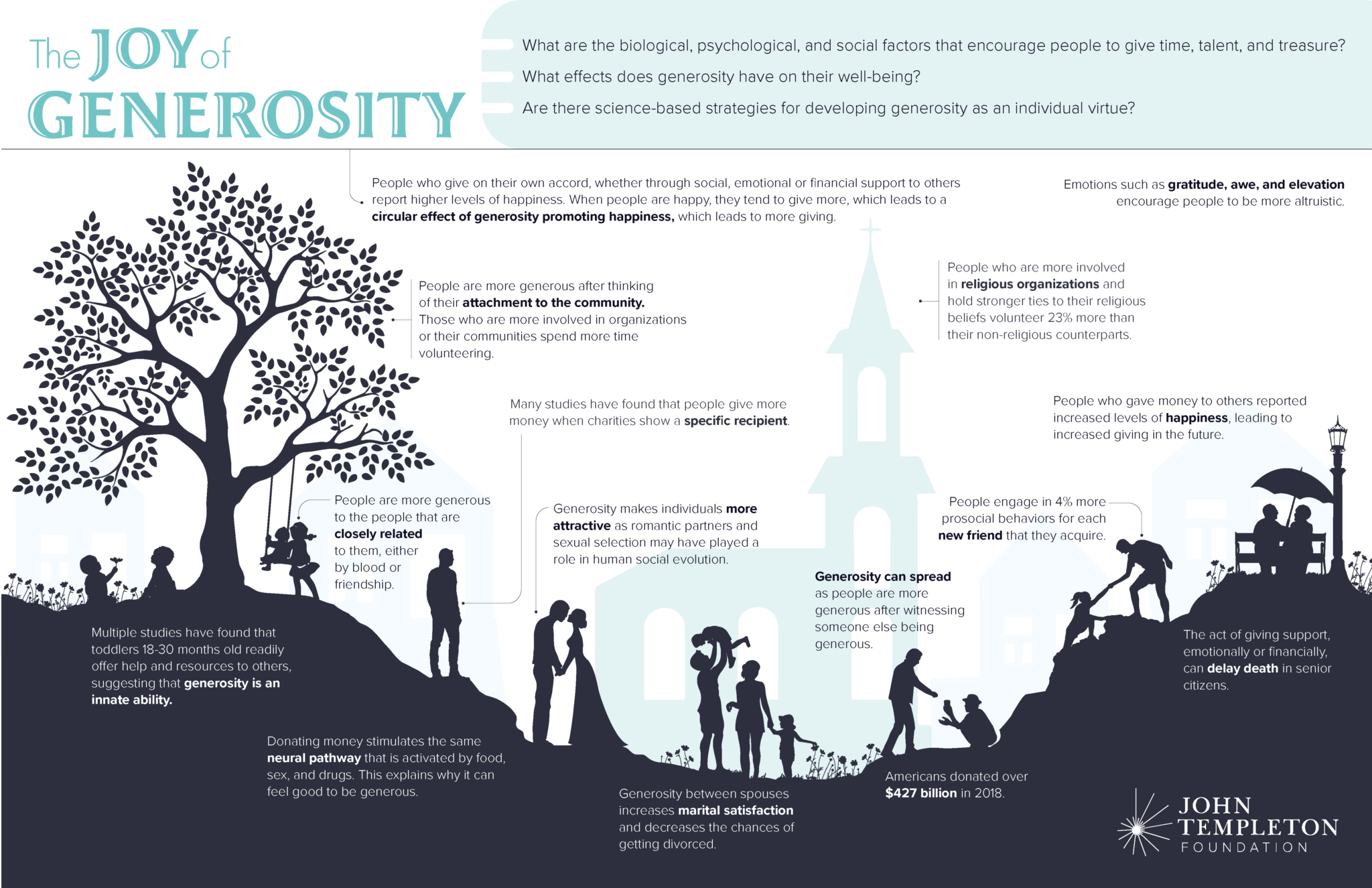

Explore 15 benefits of generosity in this infographic.

THE ROOTS OF GENEROSITY

We are a generous species. After decades of research that assumed human nature to be intrinsically selfish and aggressive, recent years have seen the emergence of a more complex and nuanced understanding. While studies suggest that humans have a propensity for self-interest, research has also revealed that currents of generosity run deep within us.

Indeed, generosity has its roots not just in our individual development but also in our biology and evolutionary history. Diverse species have been shown to exhibit forms of generosity, or what is broadly described as “prosocial behavior”—acts that benefit others. The pied flycatcher, a sparrow-like bird, will risk its life by mobbing predators to drive them away from other, biologically unrelated members of the species. Vampire bats will reciprocally share blood with both biologically related and unrelated bats. Rats will actively engage in behaviors that alleviate a fellow rat’s distress. In one study, chimpanzees helped an unfamiliar human without receiving a reward, even when assistance required substantial physical effort. Such displays of generosity across species suggest that it may be an evolutionary adaptation that has helped promote the survival of these species—and our own.

It is perhaps not surprising then that a host of studies have uncovered evidence that humans appear biologically “wired” for generosity. Generous behaviour activates the same reward pathways triggered by sex and food—a correlation that may help to explain why giving and helping feel good, and provide further evidence for the idea that prosocial activity has been an important evolutionary adaptation.

Further evidence of the deep roots of human generosity comes from studies finding consistent displays of generosity among children—even toddlers. Children as young as 14 months will help others with a variety of problems, like handing objects to a person who is unsuccessfully reaching for them. And a study of 18- and 30-month-olds found that children of both ages voluntarily engage in instrumental helping (such as helping an experimenter reach a clothespin that is out of reach), empathic helping (such as giving a cold experimenter a blanket or giving a sad experimenter a toy), and altruistic helping (such as handing over the child’s own blanket to a cold experimenter or the child’s favorite toy to a sad experimenter).

As children grow, whatever natural proclivities they have are shaped and reinforced by peer modeling and cultural norms. Three-year-olds will mostly share their rewards from a collaborative task equally, even when they could have taken more for themselves. Five-year-olds, but not three-year-olds, have been shown to increase the amount they share with someone whom they think might reciprocate their generosity.

POSITIVE EFFECTS ON GIVERS

Many studies point to the possible positive consequences of generosity for the giver. Giving social support—whether time, effort, or goods—is associated with better overall health in older adults, and volunteering is associated with delayed mortality. Generosity appears to have especially strong associations with psychological health and well-being. For example, a meta-analysis of 37 studies of older adults found that those who volunteered reported greater quality of life; another study found that frequent helpers reported feeling greater vitality and self-esteem (but only if they chose to help of their own accord).

Other studies have shown a link between generosity and happiness. For example, one survey of 632 Americans found that spending money on other people was associated with significantly greater happiness, regardless of income; conversely, there was no association between spending on oneself and happiness. Even small acts of kindness—like picking up an object someone else has dropped—make people feel happy. Generosity is also associated with benefits in the workplace (such as reducing the likelihood of job burnout) and in relationships (where it is associated with greater contentment and longer-lasting romantic partnerships). Generosity towards others has been shown to help smooth over “relational noise”—perceived unfairness that can arise from everyday misunderstandings—making it a critical ingredient for increasing relational trust.

INDIVIDUAL FACTORS LINKED TO GENEROSITY

There are several intrapersonal factors that can influence generosity. Feelings of empathy, compassion, and other emotions can motivate us to help others. One study found that empathy creates self-other overlap—a sense “oneness” with others—and reasoned that, when we help others under this state of oneness, we feel as if we are also helping ourselves.

Certain personality traits, such as humility and agreeableness, are associated with increased generosity, and a person’s tendency to engage in prosocial behavior may be considered a personality trait in itself. A person’s values, morals, and sense of identity can also affect how willingly they engage in generous acts. Feelings of awe or elevation have likewise been shown to influence generosity. In one study, some participants were asked to stand among towering eucalyptus trees and look up for one minute, while other participants simply looked up at a building for one minute. Those who looked at the trees experienced more self-described awe—and also picked up more pens for a researcher who “accidentally” spilled them on the ground.

Research suggests that gender may similarly influence generosity, although the findings from different studies have sometimes shown conflicting results. A study using self-reported data collected from 3,572 American households found that unmarried men and women displayed their generosity differently. Men’s giving was more sensitive to income and tax incentives. Men tended to give more money to fewer charities, whereas women tended to give less money to a greater variety of charities. Among those who are married, donations varied depending on who was making the giving decisions. When the male took the lead or the couple decided jointly, couples tended to give more money to fewer charities; when the female took the lead, couples gave smaller amounts to a greater number of charities. Interestingly, couples that made their giving decisions jointly gave less overall than those where one person made the decisions.

Religion, too, appears to influence individual giving. A study of nearly 30,000 people across 50 communities in the United States found that religious people were 25 percent more likely to donate money to a charity than were non-religious people. However, experimental studies have tested whether religious people give more in economic games. These experiments have had mixed results, with many studies failing to show a correlation between religious affiliation and generosity.

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL DRIVERS

Generosity is an inherently social act, and is influenced by a host of social and cultural factors. A number of studies suggest that individuals often act generously out of an expectation that their generosity will be reciprocated, or because they believe or assume it will burnish their reputation. A person’s generosity is also influenced by cultural norms, such as a society’s basic standards of fairness. Strong social networks may also influence generosity. For example, people with more friends engage in more volunteer work, charitable giving, and blood donations. What is more, generosity is contagious; it can propagate within social networks and workplaces. In an experiment carried out at a national park in Costa Rica, subjects who were told the typical contribution donated an average of 4 percent more money than did subjects who were not given a reference amount. The same study also found that people who donated in private gave 25 percent less than those who donated in public, and that giving a small gift (in this case, a refrigerator magnet) to potential donors increased donations by about 5 percent.

Other social and cultural drivers of generosity range widely. The influence of socioeconomic status on generosity is complex, with studies suggesting that both poorer and wealthier individuals are more generous, depending on the study and its context. The characteristics of a potential recipient of one’s generosity also influence a person’s decisions to give. For example, potential donors are much more likely to help a specific person with an identified need than an unknown or anonymous individual. Evidence seems to indicate that we are also more likely to help provide help for specific individuals than for groups. Intriguingly, when statistics accompanied the photo of an individual in need, donors tended to give less than when the statistics were omitted.

Geographic factors may similarly influence generosity. One study found that in the United States, the states where citizens reported the highest subjective well-being also showed the highest rate of organ donations to strangers.

Less surprisingly, parenting plays a major role in cultivating generosity. Some studies indicate that certain parenting practices—particularly role-modeling and regularly discussing generosity—may help children mature into more generous adults. Other studies indicate that engaging with prosocially-themed media, whether television, music, or video games, may lead people to behave more generously. In a study of 768 French restaurant customers, patrons who listened to prosocially-themed music as they ate were significantly more likely to leave a tip—and their tips were significantly greater than those of other patrons.

Finally, social or situational factors, such as the timing or setting of a request, can impact generosity in significant ways. In one experiment, individuals were more generous when forced to make a decision quickly; another study found that seminary students were much less likely to stop and help a person in need when they were running late to give a speech than when they had no pressing obligation. Natural settings may inspire generosity—one study even found that people behaved more generously in a room filled with plants than they did in a room without them.

FUTURE RESEARCH

There are several promising avenues for future exploration of the science of generosity. These include developing interventions to increase people’s empathy—and, thus, their generosity—toward others, as well as more rigorous studies about the health benefits of volunteering. The health problems associated with social isolation and loneliness may stem from decreased engagement of the biological caregiving system, something that could hypothetically be ameliorated with increased time spent helping others.

Charitable donations and volunteering are far from the only types of generosity, but they provide one convenient measure. Although Americans gave a record $390 billion to charitable organizations in 2016, giving as a percentage of household disposable income has hovered around 2 percent for decades. Roughly one-quarter of Americans volunteered for religious, public, and nonprofit organizations, contributing an estimated $193 billion worth of their time in 2016. But the percentage of people who volunteer each year has been steadily decreasing over the past decade in the United States and the United Kingdom. Ongoing research is uncovering practical methods for increasing such donations of both time and money. These new methods represent more than simply being a tool for more efficient fundraising: if greater generosity can yield measurable benefits for the giver, then they represent a powerful way of increasing human flourishing.

From https://www.templeton.org/discoveries/the-science-of-generosity